Six Rules For Meaningful Conversation

by Holly Vradenburgh

Good conversation is just as stimulating as black coffee, and just as hard to sleep after.

~Anne Morrow Lindbergh

Do you avoid serious conversations with people who disagree with you? Do you wade into such conversations, optimistically compelled to share Truth, but leave feeling frustrated with the outcome? Have you ever backed away from an Internet comment thread grieved by the intellectual vomit forever preserved in the digital world? Are you generally frustrated with the level of discourse you see among your friends, on social media, and in the news? Are you unsatisfied with your own ability to engage people who disagree with you in a meaningful way? If so, you are not alone. In fact, you are firmly in the 99.9% of people who are experiencing similar frustrations, especially in today’s simmering political climate.

As a general rule, conversations require more than one participant, which makes personal blue prints for successful conversations somewhat vulnerable to external influences. The following six principles, however, can set you up for success to the extent that success is within your control, and will teach you much about yourself, others, and the world in the process

- Discern the Times

Hush, please. That is enough, Margaret. If you cannot think of anything appropriate to say, you will please restrict your remarks to the weather.

~Sense and Sensibility, (Columbia Pictures, 1995)

The first rule of Meaningful Conversation is to know when to have it. Just as certain foods are not suitable for breakfast or alcohol recommended before evening, so also conversations need appropriate timing and context. Let’s assume for the moment that Meaningful Discourse involves deep conversations about politics, philosophy, theology, ethics, and social ills (obviously this is a vastly underinclusive definition). Not every environment is conductive to such conversations, yet many of us are forever testing the waters to discern if we can infuse normal chitchat with timeless maxims or esoteric uncertainty. Next time you attempt to “go deep”, engage in a little preconversational reflection.

First, consider your audience. Who is listening, and how well do you know them? Are children present? Perhaps the discussion of the ethical implications of sperm donations can wait. Is your racist uncle present? Perhaps you decide to let the embers smolder there rather than stir up fire. Is someone there who is recently divorced? Maybe we don’t talk about the sanctity of marriage and the prevalent divorce rate. Struggling with infertility? Cancer? Unemployment? Use a little empathy in discerning your audience and what topics are appropriate for their age, maturity, and situation.

Most people with average social intelligence and more than an ounce of kindness know not to bring up topics that they are aware will provoke pain or shame in their listener. It is perplexing, however, how many people risk such topics when they do not know their audience. To that end, assume the person you are talking to is lonely, childless, frustrated in their vocation, and deathly ill. Fill in a few biographical factors before making judgments about their amenability to certain subjects.

Let’s take this one step farther. Do not assume that others agree with your politics, religion, or regional football preferences. Perhaps the term “liberal wacko” falls differently on progressive ears than it does on your own, or “conservative bigot” just doesn’t resonate with your Republican audience. Let the person you are engaging be a blank slate that they are free to fill in for you as they choose.

Let’s say you have evaluated your audience and gathered that they are appropriate for and willing to engage in deep, hopefully Meaningful Discourse. It still may not be prudent to begin. Consider the broader environment beyond the conversation’s active participants. Maybe someone is in a time crunch, waiting on hold with the credit card company, trying to feed a crying baby, or about to check out in a department store. Maybe the other people in the theater want to enjoy the movie and not overhear your conversation about genocide. Take a moment to consider the logistics of your Meaningful Conversation and its effect on other non-participants.

2. Learn to Listen

Questions are never indiscrete; answers sometimes are.

~Oscar Wilde

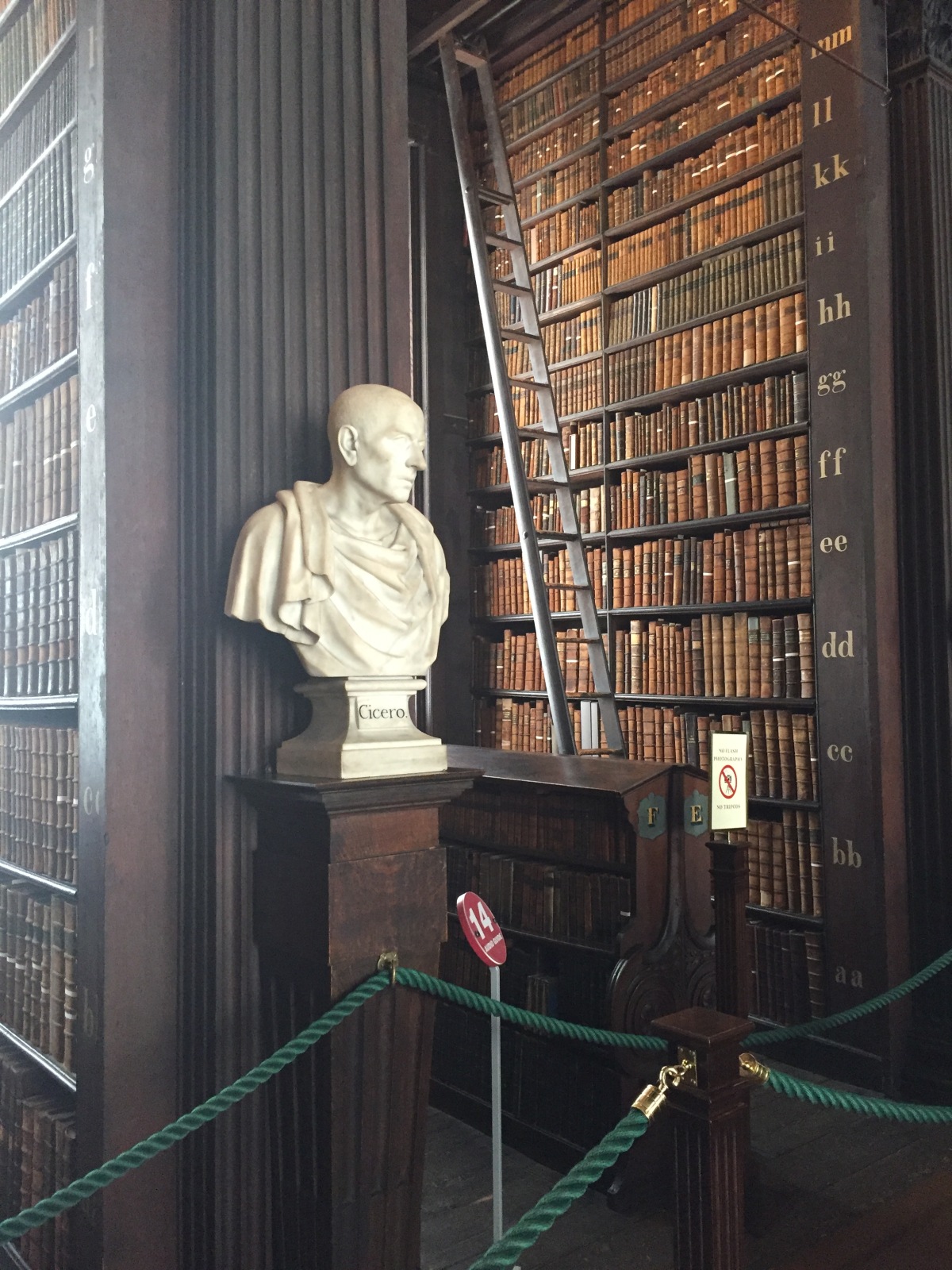

Now that you know your audience, and you are seated in a private study with snifters of brandy, all the time in the world, and no distractions, it is time to start the Meaningful Conversation. Begin by asking a question—a real question—and then really listen.

By a real question, I mean avoid this: “How could you possibly think that socialized medicine isn’t the first slippage down a slope that will inevitably land in pure Communism?” Many questions are infused with judgments, assumptions and arguments. Ask a real question–one that communicates you are genuinely interested in learning something from the other participants. By the way, saying you are genuinely interested is not the same as being genuinely interested. We have all heard the “How can you sleep at night? No, really, I’m genuinely interested!” Being genuinely interested means you think you have something substantive to learn from someone else. Driving them into a corner and badgering them to say what you think they should say can be genuinely interesting, but it does not make you genuinely interested. Try, “What is your experience with health care, and how do you think it has influenced your views on government subsidized insurance?”

After asking your genuine, open-ended question, do something truly revolutionary and remarkable: sit back and listen.

Do not merely listen for a pause so you can jump in yourself without appearing rude; do not nod your head and make eye contact so it looks like you are listening when what you are really doing is planning your next comment; do not be so set on your next comment that you fail to flow where the speaker is taking you. Instead, hear, process, ask follow-up questions, and let the other person’s comments actually inform your views, your thoughts, and your words. Listen.

3. Interpret Charitably

I always say, “Do as I say, not as I do,” unless what I’m doing is saying, “Do what I do,” in which case, do as I say.

~Stephen Colbert, (The Colbert Report)

If you find yourself listening to views that strike you as wrong or misguided and you want to respond to them, wonderful. Dialogue is a back-and-forth. But practice this principle in your answer: respond to the most charitable, yet intellectually-credible, interpretation of the other person’s argument that you can develop.

EXAMPLE: John tells Krista that he should not have to pay as much in taxes as he does, because government spending on social welfare programs is out-of-control.

Krista fills in all the gaps and hears, “I shouldn’t have to use the money that I easily earned due to my white privilege to help societal leaches obtain basic human needs” and responds to John that people who take advantage of social welfare programs are not societal leaches. John hears Krista saying, “People who take advantage of social welfare programs are angels victimized by cruel and tyrannical racists like John,” and angrily responds that he has seen people on welfare who are on drugs, committing crimes, or physically capable of working. This just reinforces what Krista thought he was saying in the first place, and the argument proceeds angrily and unproductively.

Krista could have listened to John and afforded him the most charitable, yet intellectually-credible, interpretation of his argument, which is simply that he does not think he should pay as much as he pays in taxes and he believes the government is spending too much on social welfare programs. She doesn’t agree, because she personally believes in expanding government day care service and free college tuition, but she chooses to hear only that much, which prompts her to ask follow up questions (genuinely interested, remember) and listen to John’s response. “What do you think the tax bracket for people of your income level should be and how would you cut social welfare spending?”

The principle of charitable interpretation is the most important principle of Meaningful Discourse and the most seldom employed. This principle should be used whether you are reading Descartes or talking to your bartender. (Perhaps more so with Descartes, since he is not available to call your bluff on the straw man argument you just demolished.)

Charitable Interpretation means you give the speaker/writer the benefit of the doubt. Assume, at least for the sake of argument, that your fellow conversationalist does not want people dying in ditches uninsured. Assume they do not want the terrorists to win or children to die by gun violence. Every once in a while you will hear a statement that tests your ability to give the benefit of the doubt. “I don’t care how many children die as long as I get to keep my AR-15!” At that point you may be dealing with someone who has divorced his zeal from the better angel of his nature, and you may want to suggest the zeal and angel get counseling before continuing the Meaningful Conversation. In general, though, political and social disagreements have to do with differing presuppositions, blind spots, priorities, and accepted data, and isolating those differences will get you a lot farther than assuming you are talking to an absurd sociopath.

4. Know that of which you are speaking

Informed decision? Do you think this country was founded on informed decisions? Columbus thought he was in India!

~Tracy Jordan (30 Rock)

We’ve all heard the saying that if you have two people in the room, there are at least three opinions. When there is a Meaningful Conversation happening, whether in person or on social media, it is difficult to avoid having a spontaneously-generated Deeply Held Conviction on the issue at hand. If you are the sort of person who loves a good debate, you may find yourself having spontaneously-generated Deeply Held Convictions on even non-interesting topics. Suddenly, you may really care about Net Neutrality or about whether the NFL is a violation of federal anti-trust law, and you become frustrated at those who challenge your views that have been held for a whole two hours and are based on two minutes of Wikipedia research and your friend’s Facebook post.

Before engaging in conversation on a specific topic, be aware of the general breadth of the issue and what it would take to be genuinely and thoroughly informed. If the issue is use of choke-collars on dogs, a few books by acknowledged experts might be sufficient to prepare you for a Meaningful Conversation, but if we are talking about the Fourteenth Amendment, it will take more than “Due Process for Dummies” to get you ready.

To the extent possible, start with original sources and let experts guide you in contextualizing them. A good rule of thumb is not to have an opinion on something unless you have read the original source. To use a personal anecdote, to this day I do not have an opinion on the Affordable Care Act that I am willing to state publicly. I have not invested the time to read it, much less understand it, so I do not know what to say about it. I have real opinions on how much I want to pay for healthcare, how much I would like to pay in taxes, what the quality of my healthcare should be, and I do want everyone to have access to healthcare, but how we get there and precisely how the ACA succeeds or fails in these goals, I cannot tell you with any real authority.

Roe v Wade, Citizens United, Brown v. Board, Bush v. Gore—these cases have ruined many relationships and caused more than one stroke. It’s hard to find a person who does not have an opinion on them. The question “Have you read it?” tends to shut down conversations, though, because too few people can answer in the affirmative, despite their Deeply Held Opinions.

Finally, always assume the possibility that you are the one who is hopelessly wrong. Imagine looking back on yourself in ten years when you may hold different views and then act in a way that will make future you proud.

5. Allow others inconsistent views and the ability to grow

In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. But in practice, there is.

~Yogi Berra

Logic is a useful skill and should be taught in all schools, but it is inadequate when imposed on the complexity of human reasoning and experience. How often have you seen a conversation that goes like this:

Mike: Is all life valuable—every human life?

Jennifer: Yes, absolutely!

Mike: And life should never be taken except for the tragic necessity of self-defense?

Jennifer: Yes.

Mike: But you support the death penalty?

Jennifer: Yes.

Mike: So you don’t actually believe that human life is valuable.

If Jennifer says she believes human life is valuable, respect her enough to trust that she believes that. She may or may not be able to reconcile her support of the death penalty with that categorical premise, but it does not mean she does not believe the premise.

“If you believe there is evil in the world, you can’t believe in a good God.”

“If you believe all children are valuable, you can’t support the morning-after pill.”

“If you believe in social justice and racial equality, you cannot support mandatory minimum sentences.”

Whether or not the above statements strike you as true or false, the point remains that many people do believe in the presence of evil in the world and the existence of a good God; in the value of children and access to abortifacients; in social justice and mandatory minimums. They may or may not be able to reconcile these beliefs; they may or may not benefit from you alerting them to potential inconsistencies. But they do authentically believe them, and logical syllogisms, whether fallacious or not, cannot remove the genuineness of their convictions.

If you look over your intellectual and moral development, you will probably see it is a journey of identifying your own inconsistencies and attempting to bring all your convictions into a coherent framework. No matter how advanced you may be intellectually, you are not yet in a state of perfect cerebral harmony and you will continue the process of reconciliation for the indefinite future. Give others the same grace that you give yourself. Let them be inconsistent; let them grow. You may be able to expose their inconsistencies, but you should not question the genuineness of their asserted beliefs unless they give you reason to do so beyond perceived inconsistencies.

6. Be at peace with disagreement

A fanatic is someone who can’t change his mind and won’t change the subject.

~Winston Churchill

Don’t start a Meaningful Conversation unless you are content with walking away from it without a resolution or complete agreement. If it changes you, informs you, gives you something new to think about, or gives you occasion to do the same for someone else, it was a Meaningful Conversation, and complete agreement is not required.

I once went to a police dog show where the K-9 officers in training chased a man in padding down a football field at the order of their handler. What stood out to me is that every canine competitor was eager to run, attack, and bite. Some were better than others at it, but they all wanted to do it. They did not all want to let go, however. The truly great dogs distanced themselves from the competition by not only biting hard, but also letting go immediately upon command.

Truly great conversationalists know when to let go. They don’t badger people into compliance or argue past the grace period of their fellow conversationalists. They do not insist on complete harmony, agreement, or even understanding before backing off a Deep Conversation. Be the first to show kindness; be sensitive to when a conversation needs you to let off the accelerator and extend a little humor, sensitivity, or compassion; be okay with saying, “well, you’ve given me something to think about. Thank you. Let’s talk again sometime.” Change is a journey, not a moment, so don’t insist on imposing moments on people.

Incorporating these six rules into your discourse won’t bring about world peace or universal social virtue. It might make everyday people just a little smarter, though, and everyday life just a little sweeter, and who wouldn’t want that?